“Justice may bend, but it must never kneel.” That can be said of the late Justice (Rtd.) Prof. George W. Kanyeihamba’s credo.

KAMPALA, Justice (Rtd.) Prof. George Wilson Kanyeihamba, a towering figure in Uganda’s legal and political history whose judicial independence, constitutional scholarship, and fearless dissent shaped national debates for decades, died on July 14 at Nakasero Hospital in Kampala. He was 85.

The cause was complications of advanced diabetes, according to a longtime aide. Kanyeihamba’s name became synonymous with principled defiance, a rare trait in a judiciary often wary of the executive’s shadow. From his role as chief architect of Uganda’s 1995 Constitution to his audacious Supreme Court rulings that rattled the powers he once served, his legacy is woven into the country’s legal and political fabric.

Born on August 11, 1939, in Kinaba, Kigezi, the eleventh child of Zakaliya Bafwokworora and Kyenda Malyamu Kyakundwa, Kanyeihamba’s rise from rural Uganda to global legal scholar mirrored the nation’s postcolonial journey. After early studies at Hamurwa Church School and Kigezi High School, he secured a law degree from Portsmouth University and later a PhD from the University of Warwick, becoming one of the few Ugandans of his generation to earn a doctorate in law.

His early career straddled academia and public service. He taught law in Uganda and the UK, including at Coventry University and the University of Wales, before returning home as a lecturer, public intellectual, and later, state attorney.

But it was in the crucible of Uganda’s political transition that Kanyeihamba etched his name indelibly. As chair of the Legal and Drafting Committee of the Constituent Assembly in the early 1990s, he became one of the principal authors of the 1995 Constitution, a document widely praised then as a model for post-conflict governance in Africa. The Constitution’s bold guarantees of human rights, separation of powers, and judicial independence bore his imprint.

His subsequent service in Museveni’s government, as Attorney General, Minister of Justice, and Minister of Commerce, reflected his standing in Uganda’s legal establishment. Yet even as a government insider, Kanyeihamba’s independence remained intact.

That independence came to the fore during his tenure on the Supreme Court from 1997 to 2009, where he delivered some of the most consequential and controversial opinions in Uganda’s judicial history.

In 2006, amid widespread allegations of vote-rigging, Kanyeihamba was one of three Supreme Court justices who declared that Museveni’s re-election was so tainted by irregularities that it should be annulled. The decision sent shockwaves through the establishment. In his dissent, Kanyeihamba wrote with unsparing clarity about the erosion of democratic processes and the judiciary’s duty to uphold the Constitution, even in the face of political headwinds.

That ruling likely cost him his seat on the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights. But for Kanyeihamba, judicial integrity was non-negotiable.

He again took a defiant stand in 2005 when armed security personnel stormed Uganda’s High Court to re-arrest treason suspects moments after they were granted bail. Kanyeihamba publicly condemned the invasion as an assault on the judiciary. The Constitutional Court later echoed his position, ruling the invasion unconstitutional, a rare instance of the judiciary rebuking state excesses.

Off the bench, Kanyeihamba remained a vigorous voice on governance, corruption, and constitutionalism. He accused the ruling National Resistance Movement of making “silent pacts with big thieves,” warned against judicial compromise, and championed free media as a bulwark of democracy.

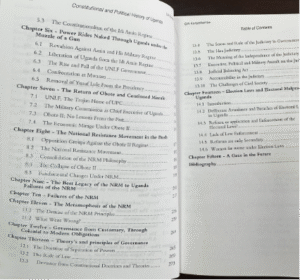

His sharpness was matched by his prolific writing. His books, including Constitutional and Political History of Uganda and Kanyeihamba’s Commentaries on Law, Politics and Governance, became required reading for legal scholars, students, and political analysts alike.

Yet despite his public ferocity, Kanyeihamba could disarm in person.

As a young accountant, I encountered him at Kampala Club, introduced by Serina Muganzi. I had braced myself for the firebrand jurist I had read about, only to meet a gentleman who seemed more interested in knowing me than impressing me. Our conversation left a lasting imprint: even the fiercest public figures can carry a quiet, genuine humanity.

In later years, declining health tempered his public engagements, but his stature only grew. He served as Chancellor of Kampala International University and Kabale University and remained an elder statesman in Uganda’s legal community.

His personal life reflected his anchored values. He was married to Susan Kanyeihamba, with whom he raised three children, Sarah, Joel, and Ruth, and an adopted daughter, Betty.

Tributes poured in from across Uganda’s political spectrum. Parliament Speaker Anita Among hailed him as a servant of the nation “on the bench, in cabinet, and in the classroom.” Opposition leader Robert Kyagulanyi (Bobi Wine) called him “a great pillar of constitutionalism in Uganda and Africa.”

Indeed, few Ugandans have straddled the worlds of power, principle, and public service with such consistency. In a judiciary often criticised for timidity, Kanyeihamba stood apart, the judge who said what others whispered, who ruled where others balked.

In a time of shifting loyalties and silenced dissent, George Kanyeihamba remained a voice both of the law and of conscience. His legacy will outlive the courtrooms he filled, the constitutions he helped draft, and the leaders he dared confront.

For a nation grappling with the tensions between authority and freedom, his life stands as a sobering and inspiring reminder: Justice may bend, but it must never kneel.

I remain as Mr. Strategy