Minister Kasaija tabled a Shs 72.1 trillion budget with revenue targets of Shs 37.2 trillion, a record 60% to be self-financed. The rest? Borrowed or begged.

Projected GDP is Shs 254.2 trillion (USD 66.1 billion) for FY2025/26, up from Shs 226.3 trillion this year. The cheer? A 7.0% growth estimate. The caution? That optimism is riding on shaky assumptions– oil dreams not yet materialised, global price volatility, regional unrest, and donor fatigue.

The structural deficit, 7.6% of GDP, remains huge.

We are witnessing a classic case of what Economists refer to as “fiscal drift” — a budget that grows but has no impact. A budget that promises industrialisation while doubling down on consumption. A budget that screams productivity but funds something else.

The macro headline looks good. But under the hood?

Uganda projected 6% growth in FY2024/25 and 7% in FY2025/26. That sounds healthy, until you interrogate the engine.

a) Agriculture’s share of GDP continues to decline. Yet 7 in 10 Ugandans depend on it.

b) Industry remains stuck at 24–26% of GDP. Despite rhetoric around industrial parks and UDC, there’s no breakout.

c) Services dominate (43–44%), especially informal trade, ICT, and financial services, which are under-recognized sectors in budget allocation.

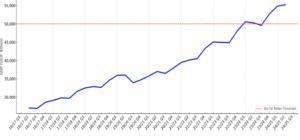

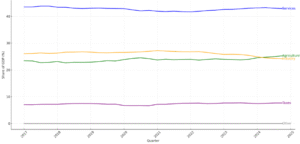

Chart 1: Uganda’s quarterly GDP at current prices, source: UBOS.

Chart 1 shows Uganda’s quarterly GDP at current prices from FY2016/17 to FY2024/25. Notice the inflexion point-despite shocks in 2020/21, the economy pushed through the Ugx. 50 trillion ceiling in 2023/24 and stayed above it. But do not be fooled by the slope. The real question is, how much of that growth is structural, and how much is subsidy-fed illusion. The GDP trend reminds us that the budget is not the economy. It is a signal. And unless we build institutions that can convert allocation into transformation, all we have is a steeper line with a hollow core.

The real budget priorities? Look at the allocations, not the slogans.

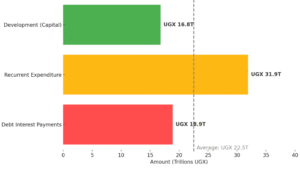

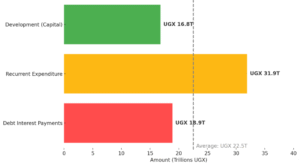

Out of UGX 72.1 trillion:

a) UGX 18.9 trillion (26%) goes to debt interest payments — a record high. We now spend more on servicing debt than on education and agriculture combined.

b) UGX 31.9 trillion is for salaries, travel, and other recurrent expenses–non-negotiables that eat away at policy flexibility. Far exceeds the average, locking the budget in maintenance mode

c) Only UGX 16.8 trillion is earmarked for development — a decline from last year. Capital expenditure is being squeezed just when we need to build. This is the budget’s weakest muscle, yet the most important for economic growth.

Chart 2: Uganda’s 2025/26 budget (UGX72.1T) priorities; source Budget 2025/26.

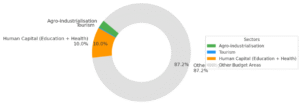

Priority sectors? Let’s be honest.

a) Agro-industrialisation gets UGX 1.86 trillion, less than 3% of the total budget. That’s a rounding error in a country where food security is both an economic and political issue.

b) Tourism gets UGX 194 billion, barely enough to resuscitate a sector ravaged by COVID-19 and undercut by regional rivals.

c) Human capital (education + health) receives modest increases, but without reforms in delivery, we are pumping water into a leaking bucket.

Chart 3: Budget allocation by sectoral priorities; source: FY2025/26 Budget

The Parish Development Model remains heavily funded (UGX 3.3 trillion), UDB has got a huge boost with Shs 1 trillion, and countless other well-meaning programs, but without rigorous return on investment (ROI) frameworks, clear outcomes analysis, we risk repeating the same leakage patterns as previous community-based funds (NAADS, OWC, Emyooga).

Policy misalignment– a budget stuck in narrative lag

Uganda has budgeted for yesterday’s economy. The world is moving toward high-value services, digital trade, energy transition, and AI-driven productivity. Uganda is still betting on subsistence agriculture and roadside enterprise. Take a closer look:

a) The fastest-growing sectors (services, ICT, fintech) receive the least strategic public investment.

b) The most funded sectors (agriculture, public admin, debt) show the lowest output growth.

c) Digital transformation is praised, but not adequately resourced. Rural last-mile connectivity, digital skills, and regulatory modernisation are not funded at scale.

Debt is no longer neutral. It’s strategic dead weight.

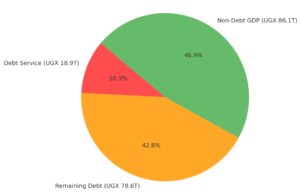

Our country’s public debt is now UGX 97.5 trillion, or 53.1% of GDP. Servicing that debt consumes over UGX 18.9 trillion this year alone.

Chart 4: Uganda’s Public Debt and GDP Composition (2025/26)

That’s not a red flag. That is running on a spare tire.

More troubling, a significant portion of Uganda’s debt is now short-term, domestic, and expensive. This has two consequences:

- a) Crowding out private investment — commercial banks prefer risk-free government securities over real sector lending. You can see the shift in business models of most banks, less private sector lending.

- b) Mismatched debt maturity vs. project ROI, we borrow short, spend long, and earn slowly. That is a fiscal time bomb.

The productivity gap, Uganda’s unspoken crisis

At the heart of Uganda’s economic underperformance is one hard truth– our productivity is too low to sustain our ambitions. Let me say that again– our productivity is too low!

- a) A farmer in Mbarara or Hoima produces one-tenth the yield of his counterpart in Vietnam. This is mainly due to poor farming methods and a knowledge gap, not muscle strength.

- b) A public servant in Kampala consumes more budget than the average SME in Jinja generates in profit. Imagine a Minister travelling daily to and fro work with two manned escort vehicles, free security at their home, etc, that is more than the average pay for a 10-staff SME.

- c) A university graduate in Lira is not employable, not because they lack a degree, but because the degree is misaligned with market needs.

This is where the budget must intervene. Not with handouts. But with systems that raise productivity per shilling spent.

Below is what the top 1% of governments do differently;

- a) Shift from input-based budgeting to outcome-based budgeting. Every line item should answer: “What productivity improvement does this deliver?” For example, UGX 1 billion in PDM must show income uplift across the beneficiaries, not just the number of SACCOs or VSLAs reached.

- i) Rebalance the fiscal mix, invest in what grows. Cut recurrent expenditure by 5% – 10% annually through payroll audits, system automation, and merging agencies.

- ii) Reallocate those savings to infrastructure (energy, logistics), digital access, and skills transformation.

- b) Tax smarter, not harder. Uganda taxes consumption heavily, but leaves wealth, land, and digital income under-taxed. Expand the base by: (i) formalising informal trade zones; (ii) introducing a modest capital gains tax for high net worth segments; (iii) digital VAT enforcement through mobile money channels.

- c) Reimagine agriculture as a business, not a culture or tradition. Shift focus from subsistence inputs to value-chain competitiveness. Irrigation, cold chains, agro-processing, and export certification must be at the core.

- d) Treat services as Uganda’s 21st-century oil. Scale up investment in fintechs and their regulation, BPO hubs, tourism, and creative industries. Set up an Export Services Development Fund to support firms selling Ugandan professional expertise abroad – not the export of blue-collar services, but professional expertise.

- e) Introduce a Fiscal Productivity Scorecard. Every ministry and program should report — output per UGX 1 billion spent. Use this to inform future allocation and remove “zombie programs.”

Budgeting is not arithmetic. It’s a strategy.

Uganda’s 2025/26 budget is courageous in ambition, but conservative in design. It repeats a safe fiscal grammar in a world that demands bold syntax. To win the next decade, Uganda must budget like a startup with global ambitions, not like a legacy department without ambition.

The numbers are big. But it’s not about how much we spend. It’s about how much we unlock.

Time to stop funding comfort zones. And start funding transformation.

Imagine Namayanja Joan, a 29-year-old mother of two in Naalya. She tills a quarter-acre of cassava, walks 4 km to fetch water, and sends her eldest daughter to a UPE school with no windows. She hears the government plans to spend UGX 72.1 trillion this year — and wonders: how much of that will ever reach me? This is Uganda’s budget in 2025/26. Bold in numbers. But too thin at the bottom.

Joan doesn’t feel GDP. She feels school fees, fertiliser prices, and the price of sugar. For her, “growth” doesn’t mean anything if her cassava still fetches UGX 200 a kilo and her husband’s boda boda earnings are down because fuel costs are up.

This budget says the economy is expanding. But what it doesn’t say is that most of the growth is happening above people’s heads, in telecom towers and city malls, not in farms, market stalls, or rural clinics.

What Joan really wants is not theory. She wants:

a) A reliable rural health centre.

b) A road that doesn’t destroy her cassava on the way to market.

c) A local SACCO / VSLA that doesn’t swallow PDM money before it even reaches women like her.

This budget shows us where the Government is present, but not where it is making a difference. Here’s what I mean:

a) The Government is present in agriculture, through extension workers, fertiliser schemes, and programs like PDM. But productivity is stagnant. The average yield per acre for key crops hasn’t improved meaningfully in five years. Why? Because we fund access, not competitiveness. Because we count inputs, not outcomes.

b) The Government is present in schools, with thousands of teachers on the payroll. But education outcomes are poor. 8 in 10 pupils in P6 can’t read a P3 passage. Why? Because we pay salaries, but not for performance. We build classrooms, not futures.

c) The Government is present in roads and electricity, but too often, that presence is one tarmac mile that ends in a swamp, or a power line with no connection.

The debt story: The house is mortgaged. The roof still leaks. Our public debt, at over 53% of GDP, is high. Every month, Uganda spends more on debt than on agriculture and tourism combined. Yet we keep borrowing, even as absorption rates fall. The real problem? We borrow short, invest long, and earn late. It’s like taking a 1-year loan to build a 10-year power dam. You feel the pressure before you feel the benefit. Even worse: much of the borrowed money is used to plug holes, not plant seeds. To pay salaries, not spark innovation. To fill fuel tanks, not build export capacity.

The many Joans do not need a macroeconomic briefing. They need results.

- If this budget cannot lift rural productivity, it has failed.

- If it cannot reduce leakages in public funds, it has failed.

- If it cannot raise learning outcomes, reduce maternal deaths, or boost exports, it has failed.

Uganda has enough plans. What it needs now is a discipline of execution — a government that not only spends money but also unlocks progress. We have a big pot. What we need now is a better recipe, and the courage to change the cook.

Chart 5: Sectoral share of GDP (2016-2025); Source: UNBS Data, accessed June 2025.

From Chart 5, note:

- Agriculture continues its slow descent, despite heavy budget allocations. Falling from ~28% to ~22–24%. Uganda is pouring money into a sector whose GDP share is shrinking, not because it is less important, but because it is growing slower than others. Are the people who badly need the money receiving it?

- Industry is flatlining. The grand promises of industrialisation have not broken through. Even with billions injected via UDB and UDC, the sector’s GDP share remains stubbornly under 27%. Industry is overhyped and underdelivered. The problem is not ambition, but execution, logistics, skills, power, and integration remain broken.

- Services are the unacknowledged champion. Quietly rising above 44%, this is the real engine, yet it remains underfunded in policy. Uganda grows through mobile, fintech, trade, and tourism, but its budget is still in the hoe-and-plough era. Services must be mainstreamed. It is time to stop treating services like a soft sector. This is Uganda’s growth engine. Formalise, digitalise, and protect it.

- Taxes on Products are a stable contributor (~7–8%), reflecting growth in consumption, not production. It is a warning- we tax what is easy, not what is transformational.

- Others are the small, volatile, and mostly residual, a reminder that our national accounting hides inefficiencies in unallocated sectors, leakages, or classification errors.

I remain, Mr Strategy. For God and My Country.

Would you like me to write about the opportunities in the FY2025/26 budget? Or would you prefer an analysis of Kenya vs Tanzania’s budget priorities? If yes, comment below and repost. Which topic interests you most? Let me know in the comments