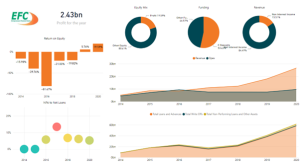

The saga of Entrepreneurs Financial Centre Uganda Limited (EFC Uganda Ltd), a microfinance deposit-taking institution (MDI), serves as a stark reminder of the imperative to fortify board structures and overall governance. In 2020, EFC defied expectations, delivering an impressive 19.6% return on equity, a surge of 2.3 times over 12 months despite the global economic downturn in Uganda. The institution also boasted a remarkable 55.1% year-on-year growth in assets, surging from Ugx. 56 billion in 2019 to Ugx. 87 billion in 2020, primarily driven by expanded lending to the informal private sector driven by the group lending credit model.

Beneath these commendable figures, however, lurked a significant flaw in credit scoring mechanisms, stemming from deficient end-to-end credit risk management processes. Summit Consulting Ltd’s State of Uganda’s Banking Sector Report 2021 underscored EFC’s precarious risk management position, labeling it as the industry’s weakest. The report pointed out critical issues such as undercapitalization, insufficient capital levels relative to risks, high credit risk exposure, and vulnerabilities to solvency shocks, all of which went unnoticed by stakeholders, including regulatory bodies.

A deeper analysis revealed EFC’s substantial exposure, with loans nearly twice the size of its deposits, posing a severe risk in the event of a collapse. The institution’s heavy reliance on borrowings highlighted the need to balance its financing sources by attracting cheaper deposits to reduce the cost-to-income ratio. However, EFC’s downfall can be traced to its failure to meet customer deposit demands, allegedly utilizing customer deposits for non-performing loans.

Every deposit-collecting institution necessitates a meticulous deposits mobilization strategy, emphasizing the importance of a balanced portfolio mix. EFC’s downfall exemplifies the consequences of neglecting this strategy, relying on attractive rates without considering the sustainability of its deposits.

Internally, EFC management acknowledged the mismatches and potential exposure but failed to secure bailouts, even identifying potential investors from Mauritius who ultimately withdrew due to the institution’s precarious financial position. This underscores a failure in strategic decision-making at both management and board levels. Challenges arose for EFC when it encountered obstacles in mobilizing group borrowers to sustain its group credit model. Before the onset of the global pandemic, this model functioned effectively, necessitating borrowers to form groups of ten individuals each to secure their respective short-term facilities lasting between six to eight months. Nevertheless, in the aftermath of the pandemic, the task of organizing these groups proved to be increasingly formidable.

The culmination of these events reveals a systemic failure in corporate governance. Foreign investors, traditionally risk-averse, have been wary of injecting additional equity into Ugandan banks, despite the sector’s promising outlook. EFC’s shareholders, notably Canadian investors, hesitated to inject additional capital, possibly due to lucrative opportunities in other markets. The reluctance to increase capital, coupled with high non-performing loans, further exacerbated EFC’s woes.

EFC’s case serves as a poignant illustration of the critical role that corporate governance and effective risk management play in sustaining financial institutions. The need for a robust governance framework, coupled with strategic risk mitigation, is paramount to weathering unforeseen challenges and ensuring the long-term viability of financial institutions.

In the aftermath of this crisis, stakeholders must reflect on these lessons and enact measures that reinforce governance structures, bolster risk management practices, and align strategies with the sustainability of deposits and loan portfolios.